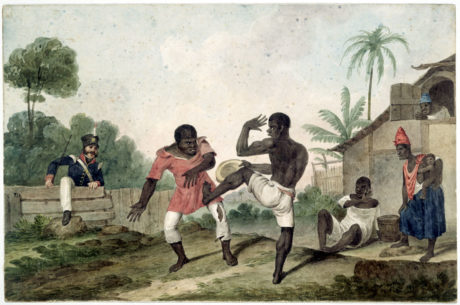

From the 16th century onward, Portugal began using African slaves in Brazil. For the most part, they came from Angola and Congo and these were mainly people from the tribes Ioruba, Daome, Guineo-Sudanais, Males, Hauça and Bantu.

The slaves were forced to work intensively in humiliating conditions; they often worked up to the point of exhaustion and were physically punished if they were not productive enough or when they made a mistake.

They were evidently not allowed to possess any weapon, but they were also prohibited from training for any form of rebellion and also, often prohibited from practicing any type of cultural expression.

Their lives were controlled and to enforce this control, the masters would mix the slaves from different origins.

It’s within these conditions that Capoeira as we know it, was probably born.

The actual reasons for the origin of Capoeira is still unknown, it is subject to various discussions and theories. There is actually a lack of documentation about the subject since the Brazilian government deliberately burnt all documents relating to facts concerning slavery in order not to drag the burden of a troubled past and recognize that the country was built on the suffering of black people.

The place, period and reasons are all interrelated and, by analyzing the history facts, we can make logical conclusions with regard to the creation and usage of Capoeira.

There are many theories with regards to the place where the slaves began to develop Capoeira:

- In the Fazenda, the place where the largest number of slaves were used but also the place where the slaves spent most of their time,

- In the Quilombos, where actual work on a rebellion and revolt took place,

- In the streets, where vendors and servants would meet, but also where many old slaves returned after they were freed.

The Fazenda and Senzala

The Fazenda was the petri-dish which gave birth to Capoeira, an art of defense hidden behind a dance form which was able to survive the slavery period because of its appearance and because it looked more like a primitive cultural art form than a fight.

Many elements were involved in its creation. The most important of them was certainly its characteristic of adaptation, which is, until today, one of the principal elements of the art. Oppressed by the slavers, the slaves had to find a tool which would not be seen as a revolt, that would allow them to develop fighting techniques, would allow them to resolve internal conflicts and also, to resolve hierarchy issues.

Capoeira was born from cultural exchanges in the Senzala (in this case, this refers to the slaves’ living habitat, the external area, and in a general context, the space where the slaves lived). The first slaves were from the Tupi tribe, and among the arts that they practiced, there was a ceremony which resembled Capoeira. We are not certain about the exact form of this art or whether it influenced the birth of Capoeira. The African slaves brought the art of N’Golo and other fighting arts with them. The interaction between the natives and the Africans is probably the initial element that gave birth to Capoeira.

Capoeira developed side by side with the oppression in the Senzala, mainly during cultural celebrations (that the owners had prohibited at the beginning of the slavery period) when free time was accorded to the slaves, as a form of ritual. Its art form was very different from what is practiced today. Even though they already had a circle, we must imagine it bigger and with a bonfire. There were observers posted around the ceremony area, who would warn of the arrival of any supervisors in the Senzala. The fight would be used as a means to prove oneself, to confront others but also to train in the transformation of something that resembled more of a dance and a ritual. Even if today’s Capoeira argues on the integration of religion, its connection to spiritual life is undeniable in various groups, and it is easy to understand its source. The Capoeira of the slaves, even though it itself didn’t include any religion, was definitely connected to spirituality.

In the evening, within the confines of the Senzala, after the long hours of backbreaking work, they would begin training on defense and revolt. They would be on the lookout of any noise that might warn the arrival of a supervisor, and they would train with an aim to escape their place of detention.

There were various revolts at the time, and without doubt, the techniques they learnt from Capoeira must have helped some of those who succeeded in escaping, in part due to the martial techniques they learnt, but also by using malice to gain an advantage.

There are certain theories regarding the origins of Capoeira which indicate that the slaves practiced in fallow fields or in open spaces within the plantations.

In any event, the techniques evolved over the years and generations, by travelling from Senzala to Senzala carried over by the slaves who were sold to other plantations and to the Quilombos when the slaves escaped, or other Senzalas when they were recaptured.

Remember that official documents rarely relate the hidden facts of a society. A theory also proposes that the slaves were used in organized combats by the owners, the same way cockfighting takes place. The other slaves would then copy these fighters, or the champions would share their skills within their community and the slaves could practice the techniques within the Senzala in hiding.

There weren’t exchanges between the natives and the Africans only in the plantations and the Senzala. The first slaves who succeeded in escaping had the option to live a hidden life in the forest, by stealing what was required from the cities in order to survive, and they would join the native tribes who would receive them or where they would form stronger independent units which would sometimes be transformed into large cities called: the Quilombos.

The Quilombos

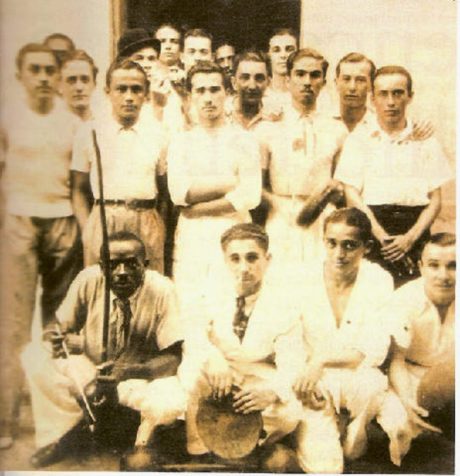

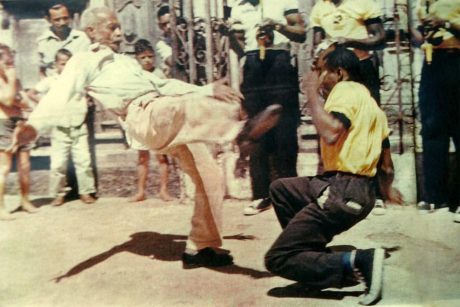

It didn’t take long for the fugitive slaves to begin establishing villages which would later be known as Quilombos. Starting out simple, life in the Quilombos gradually became more organized and structured until it was transformed into independent enclaves offering liberty, protection and the possibility of cultural development. Within this context, Capoeira had a space to grow, to flourish and become stronger. It was transformed from a survival art into a militarized defense art. They developed the techniques with a view to be able to defend themselves and also to help the bonded to free themselves. The Quilombos must have played a part in organizing revolts in the plantations.

Quilombos were places with the highest blend of ethnicity diversity and mixture. The Quilombo of Palmares had around 70 % of African inhabitants, 25 % of Brazilians and 5 % of Portuguese and other Europeans. This mixture would create a new ethnic, religious and culinary culture… This fusion also allowed for Capoeira to take a concrete form.

Note that the majority of inhabitants from the Quilombos spent some time in the Senzalas before escaping to the Quilombos and that some of them returned there once recaptured.

The cities and the streets

The cities and the streets

Capoeira was not born on the streets but it grew there, was developed there, and the streets were a place of exchange. We are talking about the cities and streets where vendors would buy and sell goods for their masters and for them. The vendors, like in any other part of the world, would often attract their clients by playing musical instruments. The Berimbau may have been one of the instruments used.

Once the goods were exchanged, instruments would set the tone for a dance or a game of Capoeira. The slaves from different owners would therefore learn from each other.

First evidence of Capoeira: 1789

In 1780, the word “capoeiragem” appeared in the police records which disturbed the authorities. The reprimands were harsh; whoever was caught doing Capoeira was put into prison, severely mutilated and sometimes even killed on sight.

The following document looks like the first written evidence of the practice of Capoeira in the cities.

It was discovered by the historian Nireu Cavalcanti in a judicial archive in Rio de Janeiro and was republished in the newspaper Jornal do Brasil in 1999.

“Adam, the mulatto boy that master Manoel Cardoso Fontes had bought a young lad, grew into a robust, hard-working and very obedient slave in household duties.

Manoel decided to rent him out as a mason assistant, a porter, or for any other hard labor. So Adam turned out to be a major source of income for his master.

With time, the shy slave who used to be fairly domesticated became more off-handed and independent and began to come back late, much later than the end of his working hours. Manoel asked repeatedly what was it that made Adam change so much — but his answers were weak and inconsistent. Until one day, fulfilling Manoel’s fears, Adam did not come home at all. He had certainly fled to one of the villages [quilombos] around the town.

To his surprise, Manoel found Adam behind the bars of the regional jail. He had been arrested with a gang of ruffians who practiced Capoeira. A quarrel had broken out that day and one of them got killed in the action. These were extremely grave crimes under the laws of the time: practicing Capoeira, and what’s more, causing a death.

The trial found Adam not guilty of the homicide, but confirmed his guilt on the charge of Capoeira, and condemned him to 500 lashes and two years hard labor in public service.

After Adam had suffered the lashes in public and labored some months in the public works, his master sent the king a plea in the name of the Passion of Christ, asking that his slave be released from the rest of his term, on the grounds that himself was a poor man and depended on the income that his slave brought him. He promised to take care that Adam would not join the Capoeiras again. His plea was granted by the Regional Judge on April 25, 1789.”

Within the societies under Portuguese rule, Capoeira was difficult to control. With the growing cities that were forming during the late 17th and early 18th centuries, larger populations resulted in larger communities of slaves in smaller areas. This produced an expanding social culture for slaves, and Capoeira dominated as a popular form of entertainment. While there were examples of it being used for self-defense, many cases were simply competition or for leisure, creating a difficult dichotomy for the ruling class to react to. Despite this, Capoeiras were punished for practicing, but the art form lived on anyway.