When we thoroughly study the sources, we see that Capoeira was not always associated with the Berimbau. When Rugendas was describing Capoeira in 1825, there were drums. When Debrét was drawing the black street vendor with the Berimbau, there was no Capoeira. In the few first-hand sources we have about Capoeira of the 19th century, there is just no Berimbau. And still, today all Capoeira Mestres and teachers do emphasize the importance of the Berimbau. The Berimbau started to become a symbol of Capoeira. When one see somebody walking around with a Berimbau, we just assume he is a Capoeirista. So, what happened in the last 100 years? Why is the Berimbau so important to Capoeira, while it was just not associated with it just 110 years ago?

Out of Africa – the Berimbau

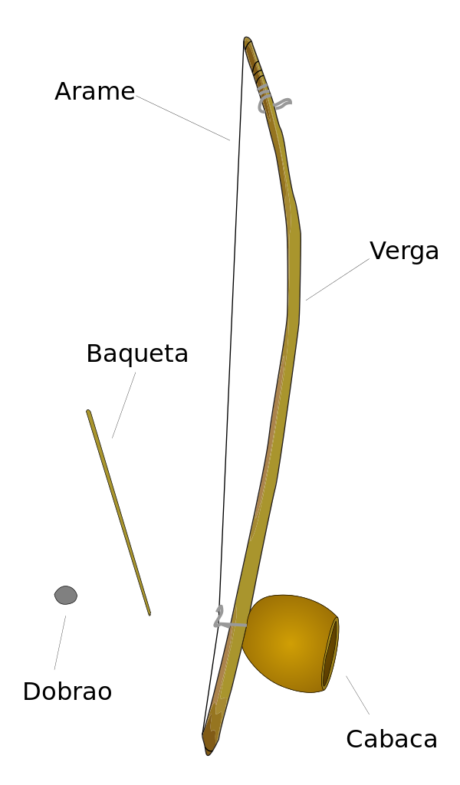

The Berimbau is an African-derived instrument. Recent and past indigenous tribes of Brazil did not have musical bows, the Europeans neither. But in Africa around the 15th century till today there was a huge diversity of different musical bows. The ones who played these bows and built them in Africa were shipped over to Brazil and there they started making Berimbaus and playing them. We find the first historical documentation of the Berimbau in the early 19th century. Especially travelers from Europe were fascinated or curious about the musical bow which was described as being used by street vendors and beggars. And it was especially an instrument used by Blacks, not by the mestizoes, not the poor whites, it was the African Brazilian people who used the Berimbau.

The first times the Berimbau was mentioned together with Capoeira, was in the early 1880’s. One document of this time (about 1891) is a description by Joao Silva da Campos, whose description was published posthumously in 1941:

The excited dark crowd performed Batuques. Samba. Capoeira circles. One heard pandeiros, cavaquinhos, violas, harmonicas, berimbau and cadential hand clapping. It was pandemonium (Campos 1941:131).

This description, which does not seem to be the description of an insider, does definitely show us that Capoeira and the Berimbau were already in the same happenings, but maybe not specifically linked to each other. It was still mainly poor African Brazilians who practised Capoeira, and who played the Berimbau. But in one expect there is an important difference between Capoeira and the Berimbau. While Capoeira was practised in different places, the Berimbau seems to have survived in only few places. Especially in Salvador. In Rio Capoeira was practised without the Berimbau (and without the Ginga and so on), but was associated with war songs used by the Guiamos and the Nagoas. In Recife Capoeira was associated with the city’s principal music bands, but they also had no Berimbau.

Symbiosis

In the 1930’s the Berimbau was nearly extinct in Brazil. It was only played in Salvador, and here most of its players were Capoeiristas or associated to them. And then, when Capoeira did suddenly increase in popularity thanks to Mestre Bimba and the legalization of Capoeira Academies by Getulio Vargas, the Berimbau did start to be used more and more. And today, only 70 years later, the Berimbau is a symbol of Brazil, but more of Afrobrazilian culture, and, of all, of Capoeira. It is still most intimately connected to Capoeira, but has now its existence in performance and entertainment outside of it as well. Without Capoeira, the Berimbau would never had experienced such an increase in popularity in the world. And maybe, though this is speculation, it would not have survived.

But there is also the other side of the coin. Would Capoeira have survived or gained so much popularity without the Berimbau? Mind, that the Capoeiras of Rio de Janeiro and Recife, the ones without the Berimbau and stripped from many parts of Afrobrazilian culture, did not survive. Alright, this is all speculation, because, in fact, Capoeira and the Berimbau did survive. My opinion is still, that without each other, both would have been much weaker nowadays than before. They are in a symbiosis: a situation, where two different entities are closely associated gaining mutual benefit from this. Already this is a reason to respect the Berimbau and keep it in your Rodas and in your trainings.

Control

There is more to the Berimbau. The Berimbau is the Master of the Roda. Of course, yes, there are other Mestres, but in every Roda, in modern Capoeira Rodas and in traditional ones, the Berimbau does control speed and style of the game. That’s why there are different rythms, different toques of the Berimbau. That is why the Berimbau is the first instrument to play in a Capoeira Roda. That’s why every instrument can miss in a Roda, but not the Berimbau. And that’s why Capoeiristas can walk through any street and will react on the sound of the Berimbau, usually making him attent and making him search for the Roda. That is why there are all rituals around the Berimbau, why it’s at the Pé do Berimbau where we enter the Roda.

Mestre Bimba did modernize Capoeira, but he did leave the Berimbau, because it is the controlling instance in a Capoeira Roda. It is the Berimbau and the bateria of Capoeira, which did keep Bahian Capoeira under control, so that it could be playful in the first, beautiful in the second and deadly in the third game. That’s the big difference of Bahian Capoeira to Capoeira Carioca or Capoeira of Recife. That’s why it did survive.

Everybody has to listen to the Berimbau, if he does not, he doesn’t have any idea of Capoeira.

Source: https://angoleiro.wordpress.com/