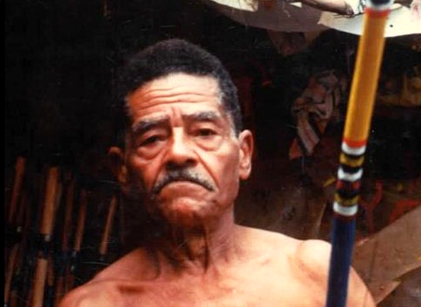

Waldemar Rodrigues da Paixão (Mestre Waldemar, Waldemar da Liberdade or Waldemar do Pero Vaz) is born in 1916 in Ilha de Maré and began the practice of capoeira in 1936 at 20 years old. He was a student of Canário Pardo, Peripiri, Talabi, Siri-de-Mangue and Ricardo of Ilha de Maré:

“I asked those men to teach me, so that I could become professional. So that I could say that I knew, and now I know. I learned capoeira,”

He began to teach capoeira in 1940, He was already a very skillful and respected capoeira when he begun holding his rodas in the Corta-Braço slum (a very poor neighborhood in Salvador Bahia), later known as Liberdade.“Earlier, it was in open air. Later I made a shed of straw and the capoeiristas of Bahia all came there to play.”

Like Canjiquinha and others, Waldemar learned capoeira intuitively, in the old way of teaching/learning capoeira by observation and imitation as opposed to systematized teaching.

Little by little, Mestre Waldemar’s roda became one of the most important meeting points for Bahian capoeiristas.

Although capoeiristas often arrived at the roda armed, they would respect Mestre Waldemar by going to the bar and asking the bartender to hold on to their weapons while they played. Waldemar didn’t have to use authoritarianism to impose control.

In a time of ‘tough capoeira’, Mestre Waldemar never carried weapons, his only defences were to never speak badly of anyone and promote a high level of discipline from his students. He thus maintained a high level of respect from other capoeiristas and mestres.

“I always wanted to stay out of brawls, out of trouble. I hold this value even today. Everyone appreciates me, everyone likes me. If you go here and there, you won’t find anyone who speaks badly of me, in any subject. I know how to treat everyone well, I don’t mistreat anyone.”

Mestre Waldemar, besides being a great player, was also known as being one of the greatest singers of Bahian capoeira: “I still have pride in my throat, for singing my ladainhas. Songs of capoeira angola. I didn’t find anyone who sang more than me. I still don’t.”

Mestre Waldemar taught his students through the experience of playing in the roda, he would signal to his students with gestures, determining the movements that they must do:

“I taught in the roda, but there were also training days. They would play and I would make a signal to do tesoura, I would make a signal to do chibata. I would make a signal for the other player to duck.”

Amongst other artists and scholars, Mario Cravo, Carybé and Pierre Verger were frequent in his Barracão. Thanks to that we have amazing sculptures, illustrations and pictures bearing the history of his capoeira.

Waldemar was a great capoeirista, but walked in the shade. He was discreet about his activities and did not seek fame. Despite his noted talent as a singer and berimbau player, he did not integrate with the tourist capoeira of the market.

In old age, mestre Waldemar suffered from Parkinson’s disease, despite this he remained active in Capoeira, recording his famous capoeira album with his good friend Mestre Canjiquinha in 1984.

Mestre Waldemar died in 1990 and is remembered as one of the greatest and most influential Mestres in the history of Capoeira.

Source: http://www.cdoscotland.com/